New Brunswick isn’t bankrupt yet. That’s the good news.

That bad news is that every year, our financial handcuffs are getting tighter. And our ability to deliver services, make real choices, and invest in important initiatives diminishes.

Here’s why.

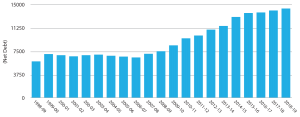

Back in 2000, New Brunswick was in pretty good financial straights. We weren’t a wealthy province but we didn’t spend more than we brought in. Our provincial public debt levels (the money New Brunswick owes to other governments and financial institutions) remained pretty steady. In fact, some governments even managed to make payments on our debt and bring it down.

But then, something changed.

In 2008, there was a global financial crisis and New Brunswickers felt the crunch. The New Brunswick government began a program of “stimulus spending” to prop up our economy.

Stimulus spending is an economic strategy used by governments to try to reverse economic recessions (periods of negative growth in gross domestic product). The theory (developed by John Maynard Keynes) rests on the idea that our economy is driven by the demand (e.g. spending) of individuals, businesses, and government combined. When individuals and businesses lose some of their ability to spend (i.e. during a global credit crunch), government needs to step in and spend more to make up the difference.

So they did. Our biggest budget deficit in history was in 2009.

The problem? Government spending didn’t slow down when the global economic crisis eased. Between 2008 and 2018, New Brunswick DOUBLED government debt levels.

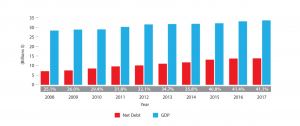

We’ve doubled the debt but we’re slow on growth

Government debt in itself isn’t necessarily a problem. All governments have debt— that’s how they fund infrastructure over the long-term. When you build things that cost millions (and billions) of dollars, you don’t pay cash— you finance it. So governments will always have debt.

Like any debt, you have to be able to pay it back. New Brunswick’s ability to pay back its debt is measured a number of ways. But one of the most important things to look at is our debt-to-GDP ratio or DEBT BURDEN. If our GDP (the value of all the goods and services we produce) was growing like crazy, our debt levels wouldn’t matter so much. But our debt levels are growing MUCH faster than our GDP.

Take a look:

Since 2008, our debt-to-GDP ratio has risen from a manageable 25.1% to 41.1% in 2017. That’s a problem.

So what do we do?

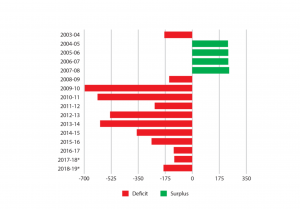

Seems obvious. To stop our debt levels from rising faster than our GDP, we have to stop spending more than we bring in. When a government spends more than earns in taxes and transfers, it’s called running a deficit. When governments spend less than they bring in, it’s called a surplus.

Here’s a look at how our government has been managing its annual budgets over the past 20 years:

The red lines represent annual deficits. The amount of the deficit gets added to our provincial debt. The green lines represent surplus budgets. Sometimes the surplus gets applied to the debt to pay it down. Other times, governments spend the surplus.

New Brunswick has a spending problem AND a revenue problem. We simply can’t spend as much as we have been. BUT we can’t just rely on spending cuts to get us where we need to go.

We also need to bring in more revenues— you can do that by either growing the economy, raising taxes, or asking for more federal transfer payments from the Federal government.

Asking for more money from the Federal government is a long, painful (and usually unsuccessful) process. And our tax burden is already higher than other comparable provinces. We can’t tax ourselves to the point where we are uncompetitive and can’t attract people or investment.

So that leaves us with a combination of growing the economy and cutting the growth in spending. Growing the economy doesn’t happen overnight. It requires a focused vision and a long term plan.

And that’s what the next provincial election MUST be about. Every voter, every politician, and every policy maker must be focused on making the decisions that will grow our economy in the long term, while knowing where and how to cut spending so that it doesn’t compromise that vision and impede the very growth we’re trying to achieve.

Stay tuned for our next blog post about where the money comes from and where it goes.